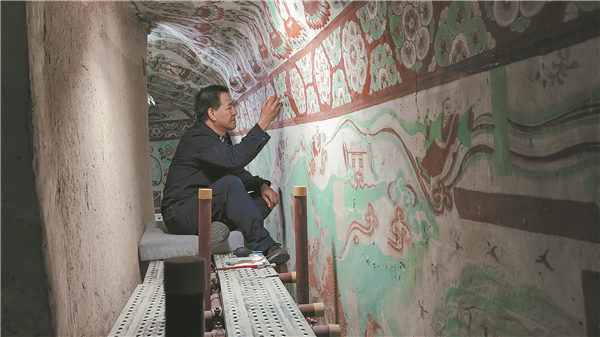

The Master of Dunhuang, a documentary franchise about those dedicated to the cultural protection and heritage of the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang, Gansu province, features Yang Tao, a veteran grotto restorer. [Photo provided to China Daily]

Documentary's second season shines an intriguing light on those who work in Mogao Caves, Xu Fan reports.

Near the end of July, during peak tourist season, the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang, Gansu province, were bustling with tourists. However, a small team of mural restorers quietly carried out their routine, seemingly undisturbed by the constant stream of visitors just a short distance away from their workplace — Cave 196.

Yet to be opened to the public, the cave, which dates back to the late Tang Dynasty (618-907), is situated on the top floor of the cliffs that were carved into the Mogao Caves, the world-renowned treasure house of Buddhist art.

Yang Tao, a seasoned grotto restorer who has worked in Dunhuang for more than three decades, ascends the stairs to the cave each day as part of his essential routine.

His regular job, most of the time, includes coaching apprentices, with the youngest born in the 2000s, checking the damaged areas, and researching restoration methods. Additionally, Yang sometimes examines recorded videos from the infrared cameras to see if there are any uninvited "guests", for instance, a curious pheasant or a naughty stray cat.

Even during his spare time, the veteran demonstrates his passion for Dunhuang and its distinctive landscape. He heads into the Gobi Desert, taking aimless strolls and collecting seemingly useless items, ranging from dried poplar branches to stones, as "souvenirs".

His story is featured in the first episode of The Master of Dunhuang, a Tencent News documentary franchise that began streaming its second season online on Oct 11.

Continuing in the style of the first season, which aired last year and attracted a large viewership, the new season sheds light on ordinary people dedicated to preserving the centuries-old grottoes and the heritage of Dunhuang culture. It consists of six episodes that recount three tales about grotto restorers, the artists who replicate murals, and tour guides, respectively.

For Yang, one of Dunhuang's most experienced restorers who still works on-site, restoration work is akin to performing intricate surgery. He meticulously tends to the damaged parts, treating them with care and attention, as if they were elderly patients in need of surgery.

Yang's apprentice Mao Jiamin, working in the Cave 196. [Photo provided to China Daily]

One of his most challenging tasks is restoring a large piece of a ceiling mural that has bulged out due to decades of dust accumulation. Through intensive research and discussion, including a study of the first restoration conducted in 1953, Yang and his fellow restorers have decided on a conventional method — mixing and stirring mud and linen to create a unique "glue" to carefully reattach the displaced area back to its original position.

Lu Zhenhua, the chief director of the documentary, says that the new season has a team of around 30 members to document the daily routines of the restorers, painters and guides, with filming taking place between early July and early August.

As the documentary is jointly produced by Tencent News and Dunhuang Academy, Lu recalls that they consulted the academy and were told that the new season would be better focused on the ensemble of its dedicated staff members instead of turning the lens on the department leaders.

Taking Yang as an example, Lu says that the crew has not only followed the restorers working inside Cave 196, but also paid attention to the expert team in the background, which consists of around 300 members. The team provides comprehensive technical support with laboratory studies, ranging from analyzing the murals' color and proportion to the restoration techniques.

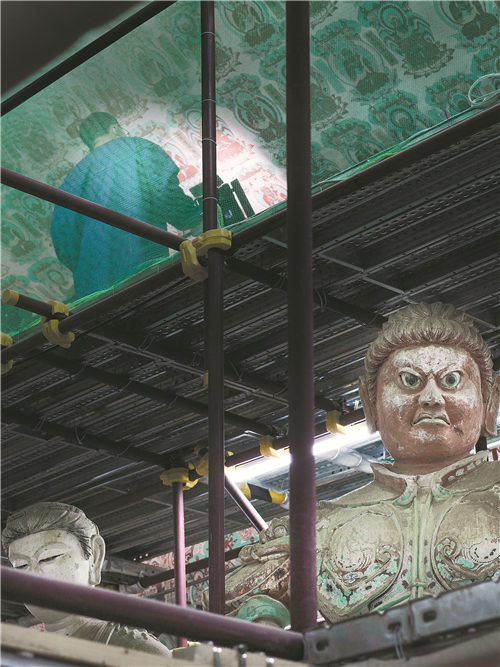

Advanced technologies also make the preservation of heritage and relics more precise. The painters who replicate murals can now utilize instruments in laboratories to analyze the pigments that have turned black due to sandstorms and oxidation after centuries.

"They also use special facilities to see through the outermost layer and discover how the original murals were delineated," she explains.

Despite the increasing usage of high-tech solutions, the work accomplished by humans is irreplaceable. For instance, the Dunhuang Academy has recruited a total of around 300 guides, as all tourists need to be accompanied by a guide to enter a cave.

Featured in one of the three tales, Liu Wenshan, a veteran guide who has worked at Dunhuang since 2000, has always cherished the moment of unlocking the door to a cave for visitors.

Born in the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region, Liu relocated with his parents to Yumen in Gansu province when he was a third-grader in primary school. He stumbled upon a book about Dunhuang murals at a classmate's home and was deeply attracted to the stories.

In April 2000, Liu was recruited as one of the fresh graduates to work as an intern guide. "We were only trained for one day and were required to start working the next day, as the May Day holiday began, bringing in a flood of tourists," Liu recalls.

Over years of diligent effort, from learning appealing interpretations from experienced guides to studying Japanese, Liu has accumulated a wealth of experience serving Chinese and international tourists.

Artist Luo Yueming replicating murals. [Photo provided to China Daily]

"In the 1980s and the early '90s, a lot of the foreign tourists visiting Dunhuang each year were from Japan. They were usually elderly tour groups who were very polite and would bow and express gratitude after listening to the explanations," Liu notes.

At the Dunhuang Academy, some tasks like Liu's require interacting with many people, while others involve more solitary work, quietly conducted in a secluded room.

Since graduating from the mural painting department of the Central Academy of Fine Arts in 2010, Luo Yueming did not choose to seek a job in a big city like most of his classmates. Instead, he decided to go to Dunhuang to work as a painter copying murals.

On most workdays, he stays in his studio, meticulously depicting each stroke. When further confirmation is needed, he walks for over half an hour from the studio to the caves to carefully observe the murals in situ.

Luo relaxes on weekends, occasionally leaving the Mogao Caves for downtown Dunhuang city and wandering around the local markets, seeking artistic inspiration from the hustle and bustle of urban life.

Lu, the director, says: "When we approach these 'guardians' of Dunhuang cultural heritage, we find that they are very meticulous and serious in their work, but simple and humble in their daily lives. Their love for the site withstands the test of time."

Liu Wenshan, veteran guide [Photo provided to China Daily]